June 13th, 2023

Guy Saupin

With more than a million captives shipped (8.5% of all deportations), the Spanish flag ranked fourth in the Atlantic African slave trade, far behind Portugal/Brazil and Great Britain, which was quite similar to France. The profile is highly distinctive, with two uneven peaks: the first between 1540 and 1660 (22.6%), and the second between 1810 and 1867 (72.7%). The system is just as specific. Spain was a pioneer in the use of external service providers, and became heavily involved in the 19th century, when the incumbents gradually withdrew. Although Spain banned slavery of Native Americans in the 16th century, it did not shift the issue to the importation of African enslaved labor, and this cultural heritage had no influence on the development of abolitionism in Europe.

Castile’s gradual takeover of the Canary archipelago fueled raids on nearby African coasts, providing captives for the needs of Andalucia and the kingdoms of Murcia and Valencia, and later for the exploitation of the Canary Islands. When the Portuguese monarchy set out to explore the Atlantic coast of Africa in 1434, tensions were intensified, despite papal patronage (Romanus pontifex bull, 1455). In 1479, the Treaty of Alcaçovas put an end to Castilian ambitions, forcing them to turn to Portuguese services.

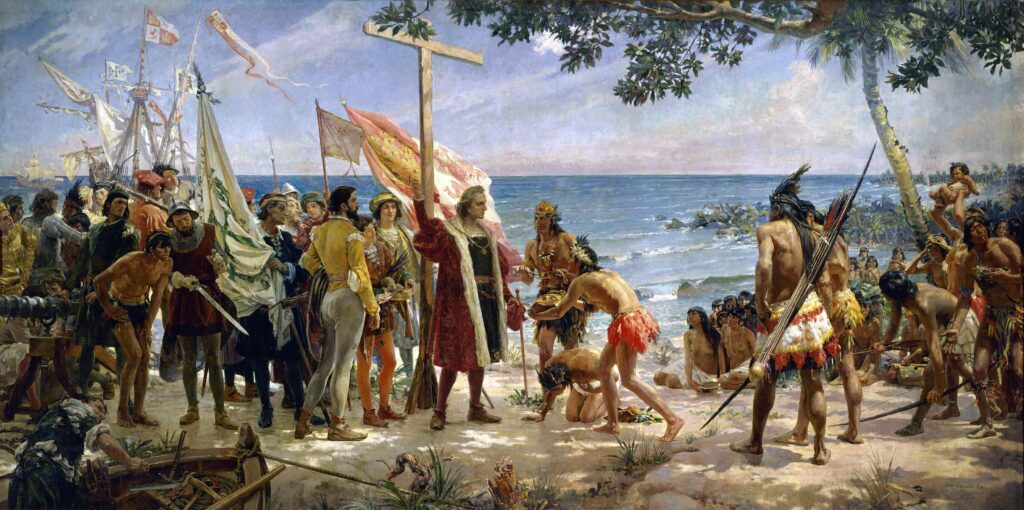

The expansion of overseas territory into the Caribbean islands, following Christopher Columbus’s expedition in 1492, soon raised the question of the human conditions required for the economic development of the Castilian Indies. The Native Americans demographic collapse, under the dual effect of the microbial epidemic and the abuse of forced labor imposed by the conquistadores, prompted the introduction of African enslaved labor, in a reproduction of the system tried out in Madeira, the Azores and the Canaries. However, for almost three centuries, the forced labor of Native American “free laborers” remained the basis for the work of extracting precious metals, the core of the imperial economic system, making the use of enslaved labor a subsidiary function.

At first, royal licenses (authorizations) were granted to leading figures who subcontracted operations to Seville-based merchants, many of them foreigners, not only Portuguese, but also Genoese and Florentine. All were obliged to use Portuguese factories. From 1533 onwards, the monarchy preferred to diversify contracts rather than rely on exclusivity. In the second half of the 16th century, the massive financial needs of Europe’s leading power forced the return to substantial monopoly contracts, amid fierce rivalry between the great merchants of Seville (1552, 1579) and their competitors from the Portuguese Judeo-Converse diaspora (1556).

The 1582 union of the crowns of Spain and Portugal placed Philip II at the head of the largest colonial empire in history. This context favored the development of a more extensive form of asientos (contracts), almost all of which were subscribed between 1595 and 1640 by the Portuguese Sephardic Jewish or New Christian network.

Portugal’s War of Independence (1640-1668) forced the company to look for new suppliers, first the Dutch and then the English, even if this raised a religious dilemma for the Catholic monarchy. This strategic dualism clearly favored the Dutch WIC (West India Company), which transformed the island of Curaçao into a delivery hub for the Spanish empire via Cartagena de Indias, Portobelo and La Vera Cruz, generating ever more intense smuggling, involving the local American administration as well as Cadiz, the technical base of the monopoly. Once again, the state’s financial crisis forced a return to asientos after an initial phase of diversified licenses. The main beneficiaries were WIC, but also the British Royal African Company from its outposts in Barbados and Jamaica.

The arrival of the Bourbons on the Spanish throne led to the attribution of the supply monopoly to the French Guinea Company (August 27, 1701), a major cause for the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession, which ended in 1713 with a British victory, the benefits of which were formalized in the December 9 Treaty of Utrecht, in particular through the transfer, in a much more favorable format, to the South Sea Company. At first, the monarchy was forced to accept concessions (1721), before claiming in the 1730s to increase control over English smuggling. This intensification led to a maritime and colonial war from 1739 to 1750, which ended with a treaty freeing Spain from the English monopoly contract, in return for compensation.

In 1778, the opening of the American trade to thirteen Spanish mainland ports, putting an end to the historic monopoly of Seville, then Cadiz, and the transfer of the islands of Fernando Po and Annobon from Portuguese to Spanish sovereignty, brought the prospect of a revival, which was thwarted by the American War of Independence (1775-1783, with Spain’s entry into the war in 1779). In Spain, the Compagnie Gaditane des Noirs, beneficiary of the asiento of 1765, ran into serious financial difficulties due to its lack of experience and interpersonal skills in the highly competitive African market, forcing it to fall back on supplies from foreign Caribbean islands.

The dependence on Anglo-American interests can be seen in the requirement for the Spanish asiento of 1786-1789 to be carried out by a Liverpool firm. In 1787, the Philippine Company’s attempt to diversify by trading enslaved people to the Rio de la Plata ran up against the same deficiencies and the formidable smuggling of Brazilian traders.

The royal decree of February 28, 1789 integrated the supply of enslaved peoples into the liberalized trade, but it remained difficult to get rid of foreign dependence. The Danish, British (1807) and American (1808) abolitions, coupled with Britain’s powerful diplomatic and military commitment, deeply reshaped the situation to the benefit of Spanish companies.

In the 1810s, national shipping accounted for 92% of shipments, compared with less than 13% in the 1790-1809 period. The treaties abolishing the slave trade of 1817 and 1835 were largely circumvented, the latter not being approved by the Cortes (state assemblies) until 1845, without any penalties for those involved.

Merchants in Havana played a central role in setting up operations, with links to partners in Cadiz, Santander or La Coruña, and mainly in Barcelona, but also in Bahia, Brazil, because of their good connections with the Bay of Benin. Spanish operators can be found in all the major sectors of the illegal trade, mainly the Rivers of the South, the Slave Coast and the Angola Coast. In the first zone, the Gallinas coast (Sierra Leone-Liberia) virtually became an “informal Spanish-Cuban protectorate”, dominated by the high personality of Pedro Blanco.

This massive involvement, which was against the tide of the other powers involved – except for Brazil, which had been independent since 1822 and only withdrew in 1850 – can only be understood within a context dominated by three major elements: national resistance to British imperialism, largely shared by France and Portugal; the gradual loss of colonial territories in the decades between 1810 and 1820; and the refocusing on Cuba, and secondarily Puerto Rico, whose economies were transformed by the expansion of large-scale plantations. Cuba became the first world producer of coffee and sugar in the first half of the 19th century. African enslaved labor took on a central role it did not have until the last quarter of the 18th century.

Around 1770, enslaved people accounted for less than 35% of the population of Spanish America, compared with 83/88% in the foreign islands of the Caribbean. In 1774, there were fewer than 50,000 enslaved people in Cuba. This figure doubled in 1792, doubled again in 1817, and doubled again in 1841, to reach around 400,000 by the middle of the 19th century.

After 1850, Spain was left on its own, and had to bow out in 1866. Slavery was not abolished until 1873 in Puerto Rico and 1886 in Cuba, two years before Brazil. The vast majority of economic, social and political elites supported this late, massive involvement, given the profits generated for both business investment and state taxation. As early as 1811, the Cuban lobby overcame the liberal abolitionist minority in the Cortes of Cadiz. Subsequently, the latter was maintained in a few circles, but remained barely audible in Spanish society.

Spain had no particular vision of African slavery, and its commitment to the defense of Catholicism eventually dissolved into materialistic imperial interests. However, it favored the use of Portuguese services, and then those of their competitors. For almost three centuries, African slavery was not at the heart of imperial exploitation; it only became so at the end of the 18th century, when it was drastically restricted to the large island of Cuba. It was then that Spain became a major protagonist in the Atlantic trade of enslaved people, mainly under illegal conditions according to the international agreements enforced by Great Britain.

Further Information

About the author

Guy Saupin is a professor emeritus of modern history at the University of Nantes since 2015. He is a specialist in European port cities and relations between Africans and Europeans in the Atlantic world in the modern era.

Bibliography

Almeida Mendes, António de, « Les réseaux de la traite ibérique dans l’Atlantique nord (1440-1640) », Annales, Histoire, Sciences sociales, 2008, vol. 63-4, p. 741-752.

Fradera Josep M. et Schmidt-Nowara Christopher (éds.), Slavery & Antislavery in Spain’s Atlantic Empire, New York-Oxford, Berghahn, 2013.

Rodrigo y Alharilla, Martín et Chaviano, Lisbeth (dir.), Negreros y esclavos. Barcelona y la esclavitud atlántica (ss. xvi-xix), Barcelona, Icaria, 2017.

Vila Vilar, Enriqueta, Hispano-América y el comercio de esclavos. Los asientos portugueses, Sevilla, Escuela de Estudios Hispanoamericanos, 1977.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.