July 6th, 2023

Guy Saupin

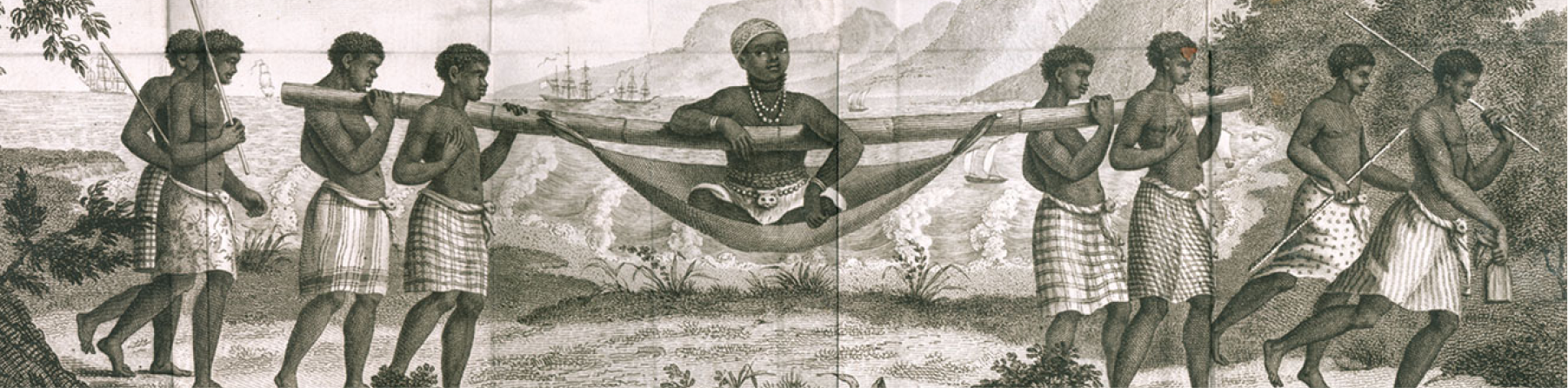

The portrait of this courtier from Malimbe (extreme north of present-day Angola), a maritime gateway to the Kingdom of Kakongo, north of the Zaire River, has been handed down to us from an engraving inserted by the captain of a Saint-Malo ship, Louis Ohier de Grandpré, in his account of the trading expedition conducted in 1785-1786, and published in Paris in 1801.

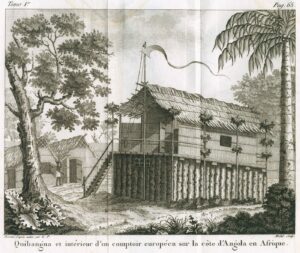

The drawing depicts Tati-Desponts as he is transported from his “petite terre”—(literally “little land”), the name given to his village and surrounding lands where he had his house, enslaved persons, and dependents—to the Bay of Malimbe, where he entered into communication with ships involved in the transatlantic trade of enslaved African peoples. The Europeans had no fort in this area and made do with quibanga, transitory trading posts, built in the African style. For sanitary reasons, the seamen-traders slept on their ships, leaving the surveillance of their cargo under African guard, controlled by the royal administration. At this time, Malimbe was experiencing the last phase of a century of intense commercial activity, in second place behind the nearby Cabinde. The Comte de Capellis wrote in 1784 that: “[African] courtiers almost all [spoke] French, English, and Dutch [hierarchy of European presence] with a truly astonishing natural ease, not knowing how to read or write even in their own language.”

Here, we see a young man, dressed in a simple loincloth—unlike his counterpart Pangon from Loango, captured in a ceremonial position—yet abundantly adorned with imported coloured glass beads, chains and rings, undoubtedly made from copper, of regional or external origin. He wears a cap (mpu) and carries a stick, signs of belonging to the elite, as his father, named Vabu, occupied the office of mafouc, defined by Ohier de Grandpré as: “the steward general of trade, forced to live in the place where trading occurred […]. He fixes the prices of foodstuffs and presides over all the markets and has the last word when it comes to negotiations.” Even if this royal office remained under the control of a superior known as the mambouc, a position reserved for a born prince, presumed to be heir to the throne, it provided opportunities for lower officers, made responsible for control of the coast, but especially for courtiers or brokers who served as intermediaries between the merchant suppliers from the interior and the ships’ captains.

In this context, several major principles emerged. It became unthinkable that a Christian could enslave a co-religionist in a Christian kingdom. This rule extended to the integrated Jewish communities. The question of Arian and Orthodox heretics and schismatics was first thought of in terms of an unpardonable fault justifying enslavement before this perspective was reversed. The followers of Islam however, were considered as infidels, with the Quran seen as derivation of the biblical message. Thus, they were perceived as the greatest enemies of Christ, thereby justifying their seizure as captives in military conquests in the fairest of wars. In contrast, pagan peoples, including African animists, did not fall into this category. Their evangelization, on the other hand, was a priority of Catholic universalism.

An analysis of the accounts from the Zeeland Middelburgsche Commercie Company (MCC) for the period 1749-1776 shows that mafoucs, who represented 5% of African sellers, accounted for 10% of transactions and the enslaved individuals on board ships. Other officers made up these numbers. Untitled merchants, who represented half of the operators, initiated only 34% of transactions for 31% of captives. According to the MCC accounts, the ten most important courtiers supplied between 110 and 391 captives over variable periods, a productivity to be compared with that of Tati Desponts who provided thirty-four to the Bordeaux ship La Manette (250 tons) in 1790, which loaded 60% of its cargo in Malimbe and 40% in the mouth of the Congo.

Transactions were conducted according to the principle of barter in an equivalence system based on units of account. Grandpré calculated an average value of fourteen “commodities” or units, broken down into “64 piezas” for one captive or pieza de Indias. In the 18th century, prices increased dramatically, even tripled, after the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). On the Angolan Coast, the demand was remarkable in terms of the importance given to Indian and European textiles. In the accounts of the MCC (1720-1796), these represent 63.8% against 57% on the whole of the African coast, ahead of weapons (21.4% against 23%), alcohol (7.1% against 10%), and miscellaneous items (7.7% against 9%). The embellished dimension to Grandpré’s illustration echoes this importance accorded to fabrics. The loincloths were most often made from imported fabrics, of European origin for the striped, dotted, or checkered designs, or of Indian origin for textiles with floral decorations.

Tati’s economic and social ascension, formalized by the marriage of his father with a sister of the king of Cabinde, which made him a brother of the new king in the matrilineal succession, aroused deep rivalries. The young Tati was kidnapped by the men of his “suzerain” (head of lineage) and exported to Saint-Domingue, where a trading captain named Desponts recognized him, bought him, and brought him back to his home country, in order to restore the climate of trust in business. The association of the two names acts as an indicator of the existence of a transcultural commercial and moral community.

While the enslavement of Muslims was perceived as the punishment of a just war, that of African animists did not fall within this framework, the purpose here being to convert them to Christianity. By blaming African societies for the taking of captives in the first place, the papacy avoided the issue of the religious legitimacy of enslavement.

About the author

Guy Saupin is a professor emeritus of modern history at the University of Nantes since 2015. He is a specialist in European port cities and relations between Africans and Europeans in the Atlantic world in the modern era. His latest work is called: L’émergence des villes-havres africaines atlantiques au temps du commerce des esclaves, vers 1470-vers 1870, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2023.

Bibliography

Ohier de Grandpré, Louis. Voyage à la côte occidentale d’Afrique fait dans les années 1786 et 1787…, Paris, Dentru, imprimeur-libraire, Year IX (1801), 2 volumes.

Albigès, Luce-Marie. “La traite à la ‘côte d’Angole’” in Histoire par l’image [online], published online in April 2007. May be consulted via the following link: HERE

Sommerdyk, Stacey, Trade and the Merchant Community of the Loango Coast in the Eighteenth Century, PhD University of Hull, 2012. May be consulted via the following link: HERE

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.