June 15th, 2023

Guy Saupin

The Christian doctrine on enslavement drew on ancient Greek philosophy and the confrontation with Islam in the Middle Ages. When Atlantic trade in enslaved African peoples was at its peak, Christian Churches lost interest in the subject and became fully complicit in it, in a surprising contrast to the criticism of the enslavement of Amerindians, voiced by Spanish theologians. Alongside the uneven influence of the Enlightenment movement, well-known Christian figures and movements played an essential role in abolitionism, particularly in Great Britain and the United States, in opposition with the virtual absence of debate on the issue in Iberian Catholicism.

Following Stoicism, an ancient school of philosophy dating from the 4th century BC, based on the ethics of intentions, Christianity took up the concept of the equality of all peoples, who were all seen as the children of God, under the authority of a single Master, their Creator. This principle was thought of as a natural right, in accordance with the divine earthly order. Nevertheless, this order had been perverted by original sin, hence the emergence of an imperfect society, in need of conversion in order to be able to return to God. Enslavement was just one feature of these imperfect societies. It was perceived as the punishment for sin. Masters and enslaved persons shared the same Master and the bible framed this relationship within a set of rights and duties. The dynamics of salvation, a permanent invitation open to all—vacillating between divine grace and the belief of the faithful, according to the Church Fathers, a key figure of whom was Augustine (354-430), bishop of Hippo (present-day Algeria)—forged the prospect of true freedom found in God. Opposing the system of enslavement therefore, would mean going against divine Providence.

The Christian Churches relied on States to moralize a society that was highly destabilized by the brutal and repeated invasions of pagan peoples from the North and East, as well as the threat of Muslim expansion from the 8th century onwards. The Christian Reconquista in the Iberian Peninsula had been counterbalanced by the powerful Ottoman Islamic conquest in Balkan Europe since the 14th century. In the West, economic and social evolution led to the decline of enslavement in favour of serfdom and above all, of a free labour market, contrasting with practices in the Southern, and especially, Eastern fringes of Europe. In Christian thought, Aristotle—a Greek philosopher from the 4th century BC and the proponent of an ethics of wisdom in a hierarchical society encompassing the master-slave binary—had a great influence on Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica (1266-1273). This naturally resulted in a stricter framework legitimizing enslavement.

In this context, several major principles emerged. It became unthinkable that a Christian could enslave a co-religionist in a Christian kingdom. This rule extended to the integrated Jewish communities. The question of Arian and Orthodox heretics and schismatics was first thought of in terms of an unpardonable fault justifying enslavement before this perspective was reversed. The followers of Islam however, were considered as infidels, with the Quran seen as derivation of the biblical message. Thus, they were perceived as the greatest enemies of Christ, thereby justifying their seizure as captives in military conquests in the fairest of wars. In contrast, pagan peoples, including African animists, did not fall into this category. Their evangelization, on the other hand, was a priority of Catholic universalism.

It was in this context that the papal bulls of the 15th century were issued. That of 1435 prohibited the enslavement of converted Guanches, an indigenous people from the Canary Islands. That of 1452 was written in the context of the fear of the Siege of Constantinople, which would fall into the hands of the Ottoman Turks the following year, and in the hopes of reviving the crusade dynamic through an alliance with African Christian princes, including the King of Ethiopia. This was added to in 1455 with another bull, which saw the monopoly of the exploration of the African coast given to Portugal, in a messianic missionary spirit. The bulls of 1482 and particularly 1493, continued in the same vein, with ultimately the famous division of the world between Portugal and Spain. The baptism of the King of Kongo in 1491 was a source of great optimism.

While the enslavement of Muslims was perceived as the punishment of a just war, that of African animists did not fall within this framework, the purpose here being to convert them to Christianity. By blaming African societies for the taking of captives in the first place, the papacy avoided the issue of the religious legitimacy of enslavement.

It is important to emphasize the singularity of the first half of the 16th century in terms of the Spanish monarchy. The clergy, missionaries, and scholars succeeded in making their voice heard by the monarchy, and despite the defensive response of the conquistadores, obtained a ban on the enslavement of Native Americans from King Charles I (Emperor Charles V) in 1542, after its condemnation by the pope in 1537. The big question remains as to why this protective dynamic did not extend to African animists. Imported as captives, they were not seen as subjects to be protected; purchased on the coasts of Africa, their enslavement was viewed as the fault of African societies and political entities.

The papacy contented itself with reiterating in 1639, via Urban VIII, the condemnation of the enslavement of Amerindians. However, the papacy had been entreated by the Catholic monarchy of Kongo since the early 17th century to reprimand the abuses of Portuguese traders from Angola. In 1657, the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith limited itself to encouraging the baptism of captives and prohibiting their sale to European Protestant traders.

The expansion of Protestantism had little impact. Neither Luther, nor Calvin, nor even less the Anglican Church were interested in the issue. Large trading companies like the Dutch West India Company or the English Royal African Company hardly called for evangelization. The increasing numbers of nonconformist sects in England and the pioneering role of some of their members in the founding of the American colonies in the 17th century did not arouse any criticism.

For all Christian Churches, the practice was considered a necessary evil, tolerated in the American colonial space, but not so in Europe. Economic interests had taken over, reducing religious discourse to a form of justifying lip service, which in itself had lost all significance, either through its subversion of the biblical message of the curse of Ham, which imagined Africans to be the descendants of the cursed son of Noah, or through its dilution in a more global approach that called for salvation from barbarism.

The chronology invites us to see the influence of the Enlightenment in the moral revolt against the trade in enslaved African peoples. The questioning of the supremacy of theology in the movement of ideas, the decline of Christianity in favour of a philosophical religion, the rise of rationalism resulting from the scientific revolution and its subsequent technical and social progress, all contributed to this awareness. The defence of human rights, for which freedom served as the matrix, was associated with that of citizenship. The duty of social utility assigned to the philosopher led to the consideration of the most serious evils, including the enslavement system.

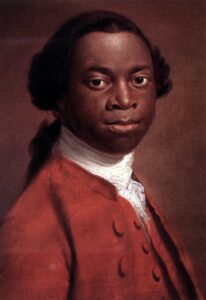

However, the first roots of a cloudy abolitionist movement comprising individuals referring to themselves as guides, were in fact, Christian, within a multi-confessional and transnational whole. Its epicentre was in Britain. The large family of non-conformist communities here provided the ideal breeding ground. The protesting heritage of the Quakers ended up putting them at the vanguard, facilitating the spread of ideas from Pennsylvania to Great Britain. However, it was thanks to the massive rallying of Methodism that a large-scale movement emerged. The great figures of Anthony Benezet, John Wesley, and Thomas Clarkson bear witness to this. London served as a melting pot to which Africans were symbolically associated. The later were former freed captives whose personal histories were marked by their insertion into these Christian movements, exceptionally going as far as abolitionist theology as was the case for Ottobah Cugoano. On the continent, profiles like those of the Swiss man Frossard or the French Abbot Grégoire, are the most striking. For all of them, activism was founded in faith; action was thought of as an instrument of God, at the service of a divine Providence.

The essential role of religious motivations in Great Britain, based on the Methodist ideal of moral awakening, in the early prohibition of the trade in enslaved peoples in 1807 was part of a tradition of defence of civil liberties, a move towards economic liberalism, and a redefinition of British imperialism. In the United States, the prohibition of the trade in enslaved peoples in 1808 was circumvented without too much difficulty until 1842, despite the law of 1820 assimilating it to piracy. The complexity of this evolution illustrates the resistance encountered by the abolitionist religious movement. The same was true in divided monarchical France with regard to its revolutionary legacy, including the abolition of enslavement between 1794 and 1802. A first combat led by an alliance of Protestant and Catholic Liberals resulted in a hardening of the fight against illegal trade in 1827, completed in 1831 thanks to their accession to power. The denunciation of this “inhumane trade” by Pope Gregory XVI in 1839, reversed positions amongst French Catholics. Traditionalist monarchists close to the pope campaigned for the immediate abolition of enslavement while the ruling liberals called for a more gradual extinction. Victor Schoelcher, by grafting on his anticlericalism, succeeded in taking advantage of the Revolution of 1848 to call for a vote on abolition, presented as a gift from the Republic, without any religious connotations.

The ambiguities of Gregory XVI’s apostolic letter, written to “turn away from the trade in Black people”, may be seen in its weak impact on even the most devout Catholic powers of the day. Portugal, very dependent on the British, only yielded in 1842; Brazil in 1850 under the threat of the bombardment of its ports by the Royal Navy; and Spain in 1866, following the abolition of enslavement in the United States at the end of the Civil War in 1864.

About the author

Guy Saupin is a professor emeritus of modern history at the University of Nantes since 2015. He is a specialist in European port cities and relations between Africans and Europeans in the Atlantic world in the modern era. His latest work is called: L’émergence des villes-havres africaines atlantiques au temps du commerce des esclaves, vers 1470-vers 1870, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2023.

Bibliography

Grenouilleau, Olivier. Christianisme et esclavage. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2021; La révolution abolitionniste. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2017.

Quenum, Alphonse. Les Églises chrétiennes et la traite atlantique, du xve au xixe siècle. Paris: Karthala, 1993.

Davis, David Brion. The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture. Oxford: OUP 1988 (1966).

Gerbner, Katarine. Christian Slavery. Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World. Philadelphia: Philadelphia University Press, 2018.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.