April 26 , 2023

Gildas Salaün

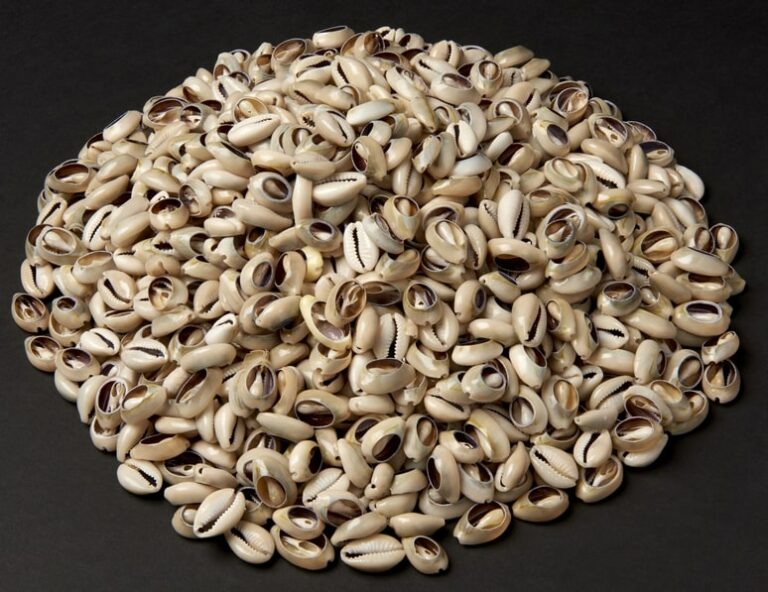

Small shells, often called bujis or bouges in French archives (a deformation of the original Portuguese) and “whitish milk in colour [and] the size of an olive” (Prévost, 1748), were imported from the Maldives to the Gulf of Guinea via Europe within the framework of the transatlantic trade of enslaved African peoples. They were adopted as a form of currency as each one was identical in size and rot-proof. Therefore, it was possible to accumulate and transport them. Moreover, their rarity in West Africa made them precious objects.

Introduced by the Portuguese in the 16th century, the cowrie emerged, in the 17th and 18th centuries, as the reference standard of the monetary system of the kingdoms along the “Slave Coast”, particularly Ouidah (Benin). European travellers confirmed that here, “[Black people] use Coris for monnoye” (Savary Des Bruslons, 1726).

The cowrie “is the most convenient currency for the trafficking of foodstuffs […]. We must not forget to supply ourselves with bujis on our voyage to Ouidah” (Prévost, 1748), because their users “have such esteem for these shells, that in trade: […] they prefer them to ‘gold’”(Prévost, 1748).

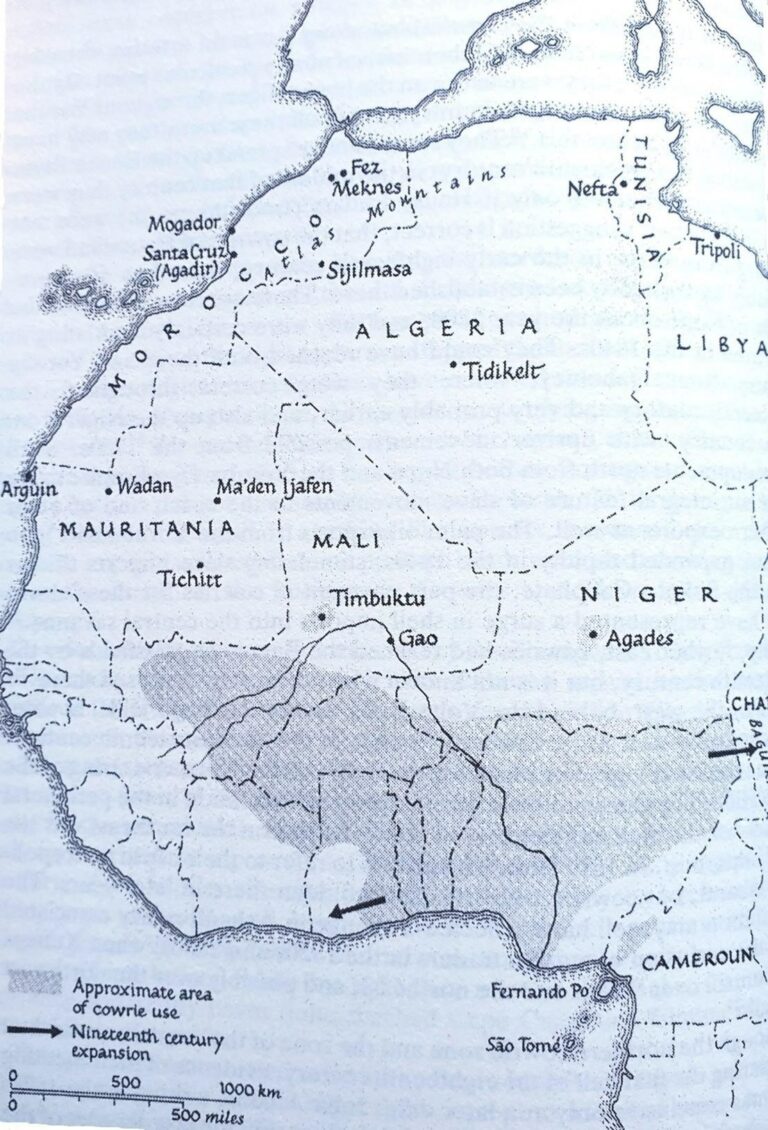

While the importation zone for cowries ranged from Senegambia to the Niger Delta, in reality, they were used as currency along the Gulf of Guinea, from Accra (Ghana) to Port Harcourt (Nigeria) and perhaps Bimbia (Cameroon). The monetary use of the cowrie was not confined to the coast, it went inland as far as the southern border of Niger, Burkina Faso, and southern Mali.

This “monetary cowrie” zone shows the commercial circuits and relationships that united the ports and their hinterland. Logically, the ports were the points of arrival of the means of payment brought by European traders (cowries) and the exit point of the merchandise sought by the former (captives).

Because of their very low unit value, cowries were mostly traded in lots. They were pierced with the help of a special heated iron and threaded on cords. The cowries were then exchanged as heavy necklaces, verified on the markets by “a Grand figure of the Kingdom, named Konagongla. This officer examin[ed] the cords; [and] if he [found] one shell missing, he confiscat[ed] them for the benefit of the King” (Prévost, 1748).

In Ouidah, there were four main multiples, designated by a special word in the local language, as well as in Portuguese and French:

In the logbooks of French ships, major transactions are generally quantified in ounces, each subdivided into sixteen sub-units called pounds (livres) or écus. Each ounce corresponded to 16,000 cowries and weighed around twenty kilos.

Finally, in the case of very large transactions, “the coris (we]re measured […] in a sort of large bushel of yellow copper, similar to a large basin, or cauldron, which can contain approximately eight hundred pounds (livres) in weight” (Savary Des Bruslons, 1726). This corresponded to approximately 400 kilos.

Europeans used cowries on a daily basis. On the one hand, to buy their food, as well as that of their captives (twelve to fifteen chickens for example could be exchanged for a cabèche (4,000 cowries) in 1752); on the other hand, to remunerate their intermediaries, such as the capita who were responsible for supervising the porters, and received “two galines (400 cowries) for each trip” and each porter, three toques (120 cowries).

But above all, cowries were essential to Europeans for the payment of customs (taxes). For example, the La Rochelle ship Roy Dahomet, which arrived in Ouidah in March 1773, offered amongst other items 615 pounds of cowries to the king and 41 additional pounds to his representative (i.e. a total of 256,000 shells!). Only after paying these customs could the Europeans begin to acquire captives, and for these transactions, cowries were once again indispensable.

As such, the cowrie is an interesting indicator that allows us to monitor the evolution of the value of captives in Ouidah: while the price of a captive was 8,000 cowries in 1724, it rose to 80,000 in 1748 (Prévost, 1748) and the captain of the Roy Dahomet even had to pay up to 192,000 cowrie shells in 1773! Thus, in half a century, the price per captive had multiplied twenty-threefold! This “inflation” has been confirmed by numerous testimonies: “formerly only about twelve thousand pounds in weight for a cargo of five to six hundred [Black people] was needed; but these unfortunate [captives] are currently bought at such a high price, & the coris are so little esteemed [here, the author is referring to the low unit value of the cowrie] in Guinea, that more than twenty-five thousand pounds are currently needed.” (Savary Des Bruslons, 1726).

All this explains why European ships embarked considerable quantities of these small shells, to the point that, when it came to goods for Guinean trade, cowries occupied second place in terms of absolute value, and were first place if we consider the volume transported.

🔶 “Coquillages contre esclaves, le cauri monnaie de la Traite atlantique”, lecture by Gildas Salaün for the Université de Nantes: HERE

About the authors

A graduate from the Université de Nantes, Gildas Salaün has been head of the numismatic collections of the Musée Dobrée since 1998. He is the author of some dozen books and numerous articles. His research revolves around the study of currencies considered as documentary sources illustrating socio-economic relations. For several years, his work has focused on the role of Nantes in Atlantic international trade. Gildas Salaün is also a deputy of the City of Nantes.

Bibliography

Berbain, Simone. Le comptoir français de Juda (Ouidah) au xviiie siècle, études sur la traite des noirs au Golfe de Guinée. Mémoire de l’Institut Français d’Afrique Noire, no. 3, Paris, Larose, 1942.

Diakité, Tidiane. La traite des Noirs et ses acteurs africains. Paris: Berg International, 2008.

Prevost, Abbé. Histoire Générale des Voyages, ou Nouvelle Collection de toutes les relations de Voyages par Mer et par Terre, qui ont été publiées jusqu’à présent dans les différentes langues de toutes les nations connues. Paris, 1748.

Savary des Bruslons, Jacques. Dictionnaire universel de commerce: contenant tout ce qui concerne le commerce qui se fait dans les quatre parties du monde par terre, par mer, de proche en proche & par des voyages de long cours, tant en gros qu’en detail. Amsterdam, 1726.

Salaün, Gildas. “Le cauri: monnaie de la traite atlantique, son usage monétaire à Ouidah (Bénin) au xviiie siècle” in Frédérique Laget, Philippe Josserand, and Brice Rabot (ed.), Entre horizons terrestres et marins, Sociétés, campagne et littoraux de l’Ouest atlantique. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2017, p. 239-251.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.