June 2nd, 2023

As a result of the overseas expansion, Portugal assumed a leading role in the development of the Atlantic trade of enslaved people. The Portuguese ships transported people across the Atlantic to Europe and the Americas. This trade became one of the most lucrative colonial activities. From 1501 until 1875, the Portuguese traffic in slaves affected an estimated 6 million Africans.

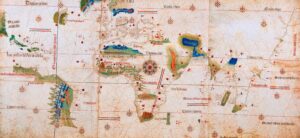

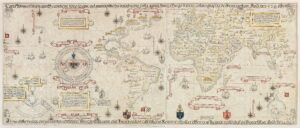

The development of the Portuguese expansion from the 15th century onward took place in the context of different economic transformations that were happening in Europe and the Middle East: firstly the development of map-making, shipping and commercial infrastructure, and secondly the political and social struggles within the country itself. The first move towards expansion was the capture of Ceuta, in Morocco, followed by the settlement in the Atlantic islands, the expeditions along the African coast, the voyage to India and the exploration of Brazil.

The Portuguese overseas expansion occurred in competition with other European powers, namely Spain, and over a second phase France, England and the United Provinces. Portugal and Castile divided the world among them through the Treaty of Alcáçovas (1479) and the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494). Presenting the doctrine of mare clausum, both treaties forbade Spanish exploration and commerce South of the Sahara and excluded the ambitions of other powers, resulting in conflicts, piracy and conquest.

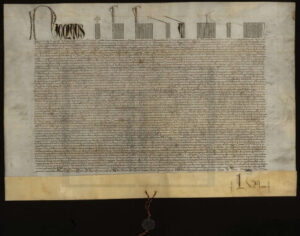

While the Portuguese were present in Africa, India and East Asia, the trade in African slaves attracted Portugal. Non-Europeans, especially the Africans, were considered as pagans and savages. Therefore, the Portuguese tried to benefit from the peoples in lands they came across as they proceeded South. The country found legal justification to enslave Africans through Papal rulings. In the bull Dum Diversas of 1452, Pope Nicholas V gave to the Portuguese King D. Afonso V the right to conquer pagans, enslave them and take their lands and goods. In 1455, the bull Romanus Pontifex extended Dum Diversas, recognizing exclusive rights to Portugal in the African expansion.

Like most of Southern Europe, Portugal was not alien to African slavery. Piracy, raids and barter along the Mediterranean were sources of slaves, namely Muslims. Already in the 14th century, Genoese and other merchants explored the Atlantic coast of Morocco and the Canary Islands to trade in slaves. Later on, in the early 15th century they went further, traveling to the Sahara cost with the same purpose.

The trade in slaves was also known amongst African societies before Portugal arrived on the continent. Local systems of exploiting labor and of buying and selling unfree people already existed in Africa. Nevertheless, Portugal would compete and supplement the existing practice with the transatlantic slave trade, in which people was forcibly transported across the ocean. Portugal took advantage of socio-political and economic conditions in Africa, namely the widespread political fragmentation, to develop a transatlantic trade in African slaves. This new slave trade transformed Africans into an international commodity and progressively established a racial order among societies at a global level.

Trade in slaves, together with gold, was among the most lucrative forms of commercial activity in the Portuguese overseas expansion. Portuguese caravels conducted direct slaving raids on the African coast, assailing villages and ravaging the land. This practice was common in the voyages organized after 1430 by Infante D. Henrique, considered one of the main drivers of the Portuguese expansion. The raiding of slaves would force the Portuguese ships to sail further to the South, allowing the extension of the knowledge about the African coast.

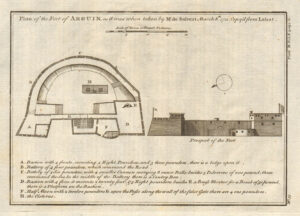

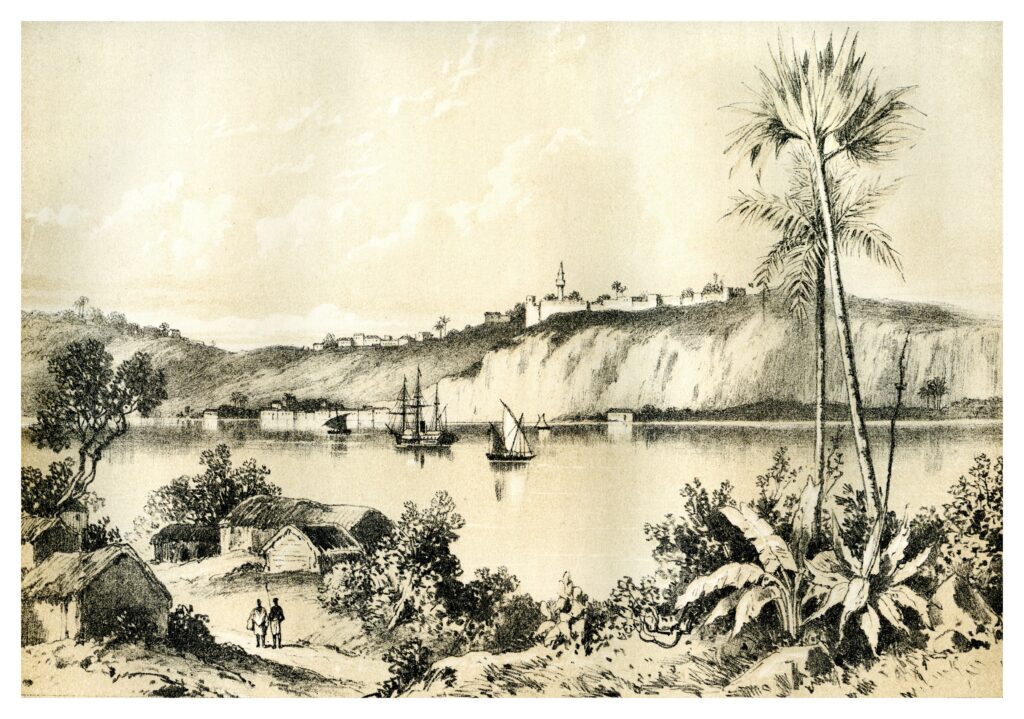

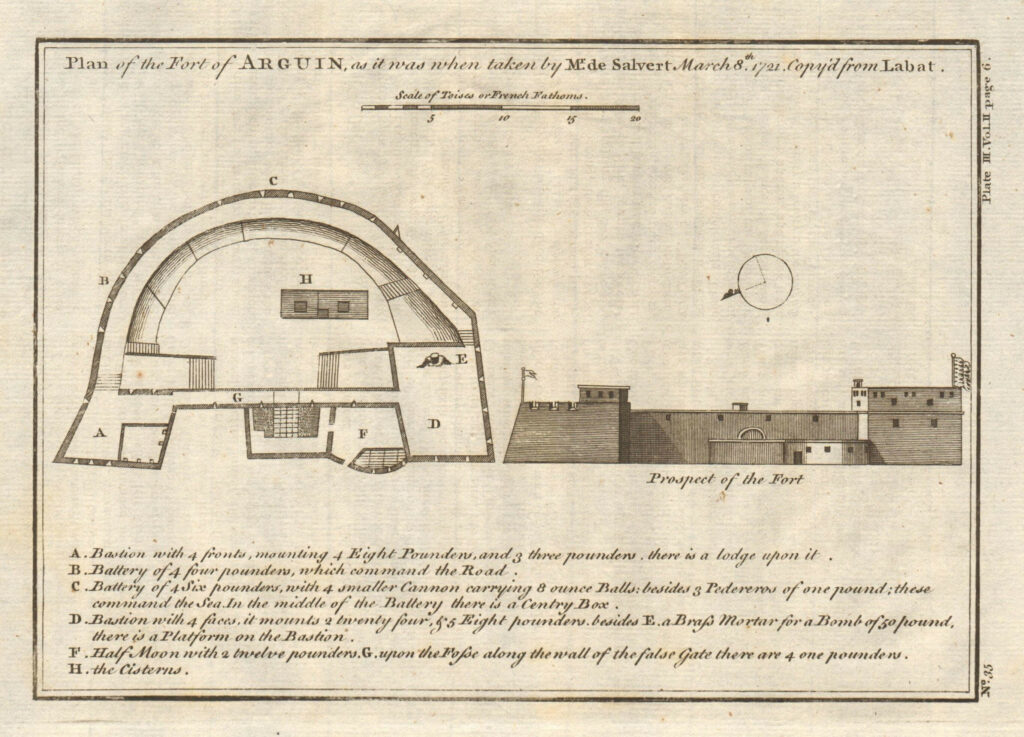

Over time, the acquisition of slaves assumed a more organized aspect, with the establishment of Portuguese slave stations on the Atlantic coast of Africa. After 1445, Portugal created a permanent trading post on the island of Arguim, from where it was possible to buy slaves. Another such slave station was Cape Verde, that in 1466 received the right to trade directly with the Guinean territory, where slaves were the most significant asset for Portugal. In the fortress of São Jorge da Mina erected in 1482, besides gold, the Portuguese engaged in slave trade with Benin Kingdom. Sao Tome and Principe, after earning in 1486 the right to trade directly with Benin, become an additional active slave trading post for Portugal. As for the Southern coast of Africa, Portugal established after 1513 a royal slave trading factory at Mpinda, in the Kongo.

From these stations, Portugal dominated the early transatlantic trade, trading in slaves in the kingdoms of Senegal, Gambia and Rio Grande, the Niger delta, Benin, Kongo, among other places. Although some communities resisted the trade, the participation of African elites in supplying slaves to the Portuguese was also common. The main sources of slaves were kidnapping, warfare, jihad, pawning, judicial sentencing and so on. The Portuguese exchanged many articles for slaves, including but not limited to food, alcohol and animals (corn, wheat, salt, horses), clothes, fabrics (cotton, silk) and commodities (cowries, shackles, silver, carpets, firearms).

Initially, Portugal used African slaves to supply the European market with unfree labor. Slaves were imported from Africa to Madeira and Azores to meet their demand for labor and rapid exploitation. Since the islands were uninhabited, Portugal employed slaves to help in the settlement in Cape Verde and Sao Tome and Principe, shaping the social fabric of both territories. In addition, Portugal mobilized slaves as part of the inter-African trade, buying captives in one territory and exchanging them in another for more profitable goods, namely gold.

By the early 16th century, initiatives to establish permanent Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the Americas increased the demand for slaves in the New World. In Spanish Americas, the Amerindian population experienced a decline after the arrival of the conquerors in the late 15th century, making it difficult to exploit their labor. An additional constraint was the protection that the Spanish crown extended to that population, defending them from mistreatment and enslavement. In Brazil, as Portugal was trying to establish an economy of plantation, raids on Amerindians for slaves proved to be inefficient to find enough laborers for European farms. With the introduction of sugar cane in the territory, attempts to find resources for sugar production helped the trade in slaves for Brazil to gather pace.

While direct arrivals of African slaves from the Iberian peninsula already existed, the first direct slave trade voyage from Africa to the Americas occurred in 1525, consisting of 200 captives transported from Sao Tome and Principe to Santo Domingo, currently in the Dominican Republic. Other voyages would follow to Cuba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, New Spain, Cartagena de Indias, Nombre de Dios, Portobelo port, to name a few places, transporting slaves namely from Upper Guinea, Lower Guinea and West Central Africa. In the beginning, slaves arrived in the Americas usually via Cape Verde and Cartagena de Indias, where the Spanish ships stopped en route to the Americas. British, French, Dutch, Danish, and Swedish merchands also supplied slaves to Spanish Americas, adding to the volume and profits of the traffic.

In Brazil, African slaves started to be imported after 1530 and the systematic slave trade voyages gained expression from 1560 onward to meet the demand for labor in the territory. Sometimes the owners of the plantations took the initiative to directly import slaves from Africa, but most of the traffic was in the hands of merchants, first Portuguese, then, in the centuries that followed, English, French, Dutch, Danish or Swedish. The merchants supplied Brazil with African unfree labor through a triangular trade in which European goods dispatched to Africa were used to buy enslaved people. Shipped to Brazil, slaves were then sold and the profits used in products to be transported to Europe. The main source of slaves to Brazil was Sao Tome and Principe and, above all, Angola where the city of Luanda founded in 1575 became increasingly predominant in the supply of enslaved people to the Americas.

With the rise of Luanda and afterward the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns from 1580 to 1640, the transatlantic slave trade assumed a new and enlarged dimension. The Portuguese-controlled slaving hubs in Africa, namely Luanda, started to trade directly with the Spanish Americas. In parallel with the official trade, the widespread contraband of slaves in which ship crews concealed captives, disembarked them in secondary ports and made unregistered voyages, contributed to the volume and effects of the transatlantic slave trade.

At the ports of embarkation in Africa, slaves were packed and stored beneath the deck of ships. The crossing of the Atlantic in the slave vessels, known as the Middle Passage, took place in inhuman conditions since the slaves faced hunger, disease and punishment, resulting in the death of some of them. After arrival at the destination, the deprivation of liberty submitted them to systems of exploitation and repression established to protect the interests of the owners. The enslaved Africans were employed in large-scale in sugar production, mines, construction, maritime labor, agriculture, animal husbandry, artisanal labor, street vending, domestic service, among other activities.

The enslaved Africans played important social and economic roles in the Americas while their territories of origin in Africa were deeply affected by the transatlantic slave trade. As the largest forced human migration in history, the transatlantic trade of enslaved people involved an estimated 10 to 15 million men, women and children between the 15th and 19th centuries. Portugal laid the foundations for this forced migration, establishing in the 15th and 16th centuries slaving networks across the Atlantic. These networks experienced further developments in the massive slave trade during the 18th and 19th centuries.

About the author

Aurora Almada e Santos is a researcher at the Contemporary History Institute of the New University of Lisbon, a leading institution in the study of the Portuguese contemporary history. Her main research interest is the Portuguese decolonization, namely the international dimension of the struggle for self-determination and independence of the Portuguese African colonies. Her current research activities include the publishing of articles and book chapters, the organization of publications and conferences, as well as the teaching of courses related to African history.

Bibliography

António de Almeida Mendes. “Portugal e o Tráfico de Escravos na Primeira Metade do Século XVI” in Africana Studia, nº 7, 2004, p. 13-30. Can be consulted online: HERE

Arlindo Caldeira Monteiro. “The Island Trade Route of São Tomé in the 16th Century: Ships, Products, Capitals” in RiMe Rivista dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea, vol. 9, 2021, p. 55-76. Can be consulted online: HERE

Arlindo Caldeira Monteiro and Antonio Feros. “Black Africans in the Iberian Peninsula (1400-1820)” in The Iberian World. 1450-1820, ed. Fernando Bouza, Pedro Cardim and Antonio Feros. London: Routledge, 2019. Can be consulted online: HERE

Arlindo Manuel Caldeira. Escravos e Traficantes no Império Português: O Comércio Negreiro Português no Atlântico durante os Séculos XV a XIX. Lisboa: Esfera do Livro, 2013, p. 369.

Malyn Newitt. A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1668. London and New York: Routledge, 2005.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.