June 9th, 2023

Emmanuel Parent

The singer Beyoncé is an international icon, whose work on memory and heritage has spread across the three continents once involved in the transatlantic trade of enslaved African peoples. In the 2010s, she succeeded in raising the question of the social memory of American enslavement within the context of a globalized and capitalist pop culture. Already in the video for “Apeshit”, she offered a postcolonial reinterpretation of certain emblematic works from the Louvre in Paris, and a similar line of questioning may be found in the film “Black is King”, partly shot in Nigeria and Ghana. With her track “Formation”, from the Lemonade album (2016), she strives to weave together the cultural heritage of colonial Louisiana with her own personal history, even if it means reviving certain forgotten spectres of the racial and intersectional question in the USA.

In February 2016, singer Beyoncé Carter-Knowles headlined the Super Bowl half-time show, the most-watched TV event of the year in the United States. Accompanied by a group of dancers whose outfits and choreography evoked the Black Panther militias and the figure of Malcolm X, she presented her latest work, “Formation”, an ode to feminist, individual, and collective empowerment. Formerly a consensual icon of pop music with her group Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé stunned America by demonstrating an affiliation with the Black political radicalism of the 1960s. The video for the song released a few days later would further reinforce the artist’s message.

Filmed in New Orleans, against a backdrop of images depicting the destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina, as well as local Creole traditions like Second Line parades and Mardi Gras Indians, this video creates parallels between Beyoncé’s militant discourse and the disasters that affect the lives of African American communities in the United States, as well as their capacity for resilience.

Like a blues song where social difficulties are recounted from an autobiographical perspective, here, Beyoncé’s life is presented as being intimately linked to the complexities in the history of Afro-descendant communities in Louisiana and the Southern United States. Facing the camera and with a powerful rap vibe, the singer opens the song with a genealogical exercise where she claims her Southern family origins, from Alabama to Louisiana, her Creole identity, and her Black pride:

“My daddy Alabama, momma Louisiana,

You mix that Negro with that creole, make a Texas bama

I like my baby heir with baby hair and afros

I like my Negro nose with Jackson Five nostrils

Earned all this money, but they never take the country out me

I got hot sauce in my bag, swag”

The phenotypic traits (hair, nose), the sociology of migration (the expression “Texas bama”, which generally designates a person from the South with a peasant look), the attachment to the South (the country), and to its culture are all evoked here. The hot sauce that she keeps in her purse, and supposed to bring her class (swag), is a marker of New Orleans Creole cuisine. In a strange staging where the destruction caused by Katrina gives way to images of the old colonial or antebellum South, ultimately it is the question of filiation (heir) and therefore, the history of enslavement of post-colonial societies in the New World, which Beyoncé challenges.

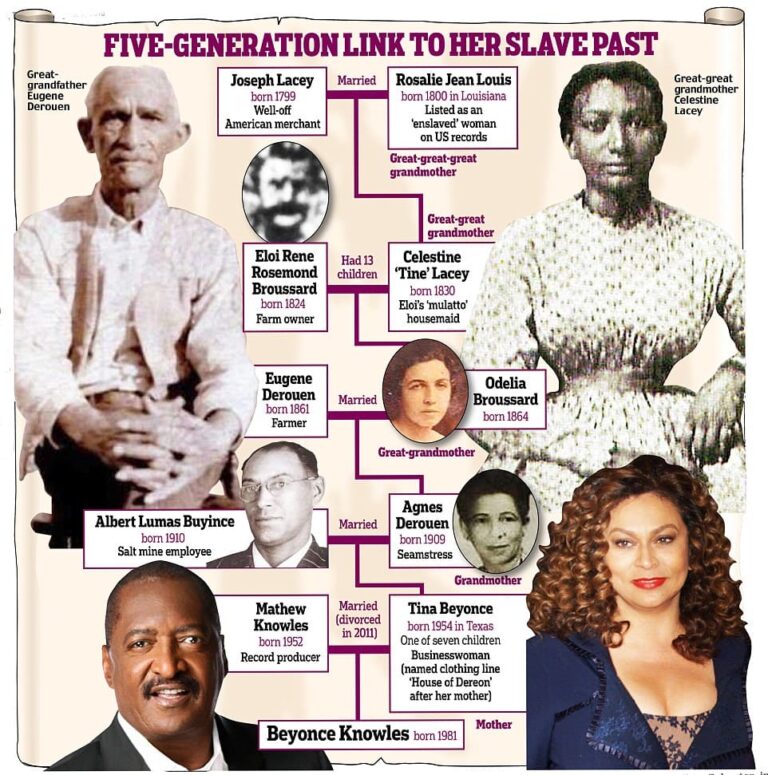

“Formation” is the final track on the Lemonade album, where constant parallels are drawn between her own individual history and the destiny of her community. She employs a narrative arc that goes from betrayal to redemption and tells how she managed to overcome the infidelities of her husband, rapper Jay Z. In the interviews that accompanied the release of the album, Beyoncé very clearly associated her marital difficulties with her family history, where troubled relationships with men were present in each generation. The known genealogy of her maternal line—a Louisiana Creole family—dates back to the late 18th century with the union between a white merchant and an enslaved Black woman. This socially unbalanced sexual relationship, which some link to the rape of enslaved Black women by their white masters, resulted in a lineage of biracial women, potentially likely to participate in the culture of “plaçage”. In Louisiana society and colonial America in general, biracial women were seen as more sexually desirable and routinely “placed” as lovers or sex slaves of wealthy Southern property owners. This was the case with Beyoncé’s great-great-maternal grandmother Celestine Lacey, the first biracial woman of the line born in 1830, who had thirteen children with her master, married to a white woman at the same time.

This racial distinction, which put a value on biracial women in the sexual market, continued even after enslavement, particularly in the realm of show business where women with fair skin and straight hair were deemed more attractive than those with darker skin. Beyoncé, the R’n’B star, is aware that she owes part of her success to the ideal of biracial beauty which she embodies for American society. She therefore inherits the problems caused by forced interbreeding, both a curse that is repeated from generation to generation, but also, and paradoxically, one of the reasons for her success. In this, her history echoes certain structures from the lives of her enslaved ancestors. With “Formation”, Beyoncé offers a narrative that superimposes a multitude of layers where personal, family, and cultural histories resonate. Here, pop music becomes the space in which the Black memory of enslavement can be staged, in all its complexity.

About the author

Emmanuel Parent is a lecturer in contemporary music and ethnomusicology at the Université de Rennes 2 in France and a researcher in the Arts Practices and Poetics research unit. His work focuses on the musicology and anthropology of African American music, from blues to hip-hop and electronic music. He is the author of Jazz power. Anthropologie de la condition noire chez Ralph Ellison (CNRS Editions, 2015) and the catalogue for the exhibition presented at the Cité de la musique in Paris, Great Black Music. Les musiques noires dans le monde (Actes Sud, 2014).

Bibliography

Tanish Ford. “Beysthetics: ‘Formation’ and the politics of style” in Kinitra D. Brooks & Kameelah L. Martin, eds. The Lemonade Reader. London and New York, Routledge, 2019, p. 192-201.

Jean Jamin. “Une société cousue de fil noir. À propos de Faulkner Mississippi d’Édouard Glissant” in L’Homme, no. 145, 1998, p. 205-220.

Emmanuel Parent. “Beyoncé, la reine et le vernaculaire” in Lili, la rozell et le marimba, no. 2, a review published by La Criée, Centre d’art contemporain, Rennes, 2021, p. 54-58.

Tracy Denean Sharpley-Whiting. “‘I see the same ho’: les figurantes lascives dans les clips, la culture de la beauté et le tourisme sexuel diasporique” [2007] in Gérôme Guibert and Guillaume Heuguet (ed.). Penser les musiques populaires. Paris: Éditions de la Philharmonie, 2022, p. 211-230.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.