June 6th, 2023

This entry describes an African-born boy who is held as an enslaved African in the port city of Lancaster in the North-West of England.

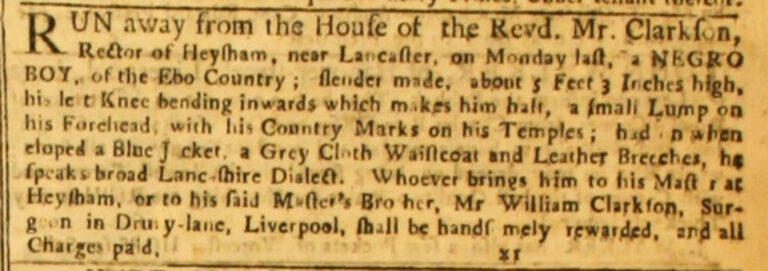

Tracing the lives of enslaved Africans in all geographies is very difficult, but in Britain records of enslaved individuals who were kept as servants is particularly challenging as household records often elide their presence. Research in Lancaster has revealed a very interesting individual who does not even have a name in the historical record so we shall name him Ebo Boy. His runaway advert appeared in the St. James’s Chronicle in London, Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser and Mercantile Register and the Edinburgh Courant showing that his master endeavoured to recapture him in locations Southward to Liverpool and London and Northward to Edinburgh. The advertisement in Edinburgh appeared in October showing he had still not been recaptured then having escaped late in August:

“RUN away from the house of the Reverend Mr Clarkson, Rector of Heysham, near Lancaster, early in the morning of Monday the 26th of August, a NEGRO BOY, of the Ebo Country, slender made, about 5 feet 3 inches high, with beautiful features for a black, his age 16 years, his left knee bending inwards, which makes him halt, a small lump on his forehead, with his country marks on his temples; had on, when eloped, a blue jacket, a gray cloth waistcoat, and leather breeches; he speaks broad Lancashire dialect. Whoever brings him to his master at Heysham, or to his said master’s brother, Mr William Clarkson, surgeon in Drury Lane, Liverpool, or to Peter Lennox, Perth, shall be well rewarded, and all charges paid; and whoever harbours him shall be prosecuted with the utmost severity of the law.”

His owner, Thomas Clarkson, was the rector of Heysham from 1756-1789 and his ownership of an enslaved African highlights that slave servant ownership in the Lancaster area spread beyond those with West Indian interests. Furthermore, his status as a Church of England clergyman clearly does not prescribe him from ownership of his fellow man that exemplifies the Church’s complicity in the Transatlantic Slave Trade which is demonstrated later by the large amounts of compensation the Anglican Church received from the British government in the 1830s for the slaves owned from the British government which amounted to 5% of the total of £20m (equivalent to £17.6 billion today). This fascinating advertisement details the ethnicity of the boy as being Igbo, an ethnic group from present-day Nigeria and describes distinguishing marks from scarification that suggests he is African born.

Such scarification marks were a symbol of prestige in Igbo culture and the fact that Ebo Boy had them suggests firstly that he was not enslaved until after he had taken part in the significant ritual which would have happened at the earliest when he was six. Brought up in Africa we can only imagine the dislocation he felt being enslaved and taken to the Americas and thence to Britain. Most enslaved Africans were sold in the Americas, Ebo Boy’s fate was different as he was brought to Britain as a domestic servant and then sold on to Clarkson. The runaway slave advert describes him as having “beautiful features for a black” and maybe within this racist description lies the clue as to why he was brought to Britain; his signature looks meant he was seen as an ideal domestic servant enhancing the prestige of his master. Clarkson’s brother, William was a surgeon in Liverpool and maybe his profession so entangled in slavery meant that it was him who supplied Ebo Boy to Thomas. We can infer that Thomas Clarkson had not treated Ebo Boy well as the limp and lump on his forehead maybe betokens previous violent encounters with his master that fully justify his desire for escape from an institution that enshrined violence.

Escaping in his servant’s clothes, he is distinctive and potentially easily spotted, but in London or Scotland what might give him away most is his “broad Lancashire dialect”. This detail highlights the significant time the boy has spent amongst Lancashire folk and how he has adapted so much that his English is shaped, not by his Colonial background, but by his Lancaster home. There might have been few black individuals in Lancaster in the 1760s but already some of them were putting down truly local roots. His Lancashire accent is the marker of Ebo Boy as an important individual for understanding the development of Black British identities as early as the mid-eighteenth century. The recovery of such important lives from the depths of the archives enable new narratives to emerge that deepen our understanding of the importance of slavery and a black presence to fully understanding provincial British culture. They show the deep imbrications of slave cultures into British homes and the deep roots of black British culture that extend to the furthest regions of the country. As for Ebo Boy himself, these related adverts are the first and last record of his remarkable life, born in Africa, taken on the Transatlantic Slave Trade via the Americas to a small village in Lancashire, making a bold bid for freedom that appears to have been successful for at least 2 months and maybe as much as a lifetime.

About the author

Alan Rice, Professor in English and American Studies, Director of UCLan Research Centre in Migration, Diaspora and Exile (MIDEX) and Co-Director of the Institute for Black Atlantic Research (IBAR) at the University of Central Lancashire, UCLan.

Bibliography

Simon Newman, Freedom Seekers: Escaping from Slavery in Restoration London, London: University of London Press, 2022. Downloadable HERE

Gretchen Gerzina, Black England, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2022.

Alan Rice, Radical Narratives of the Black Atlantic, London: Continuum, 2003.

Alan Rice, Creating Memorials: Building Identities: The Politics of Memory in the Black Atlantic, Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 2010.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.