March 27, 2023

Bernard Salvaing

The economy based on slavery shifted at the end of the Middle Ages from the Mediterranean towards the Atlantic. Sugar plantations first appeared on the islands off the coast of Africa, and then on the islands of the Caribbean (where they would reach their peak during the eighteenth century, notably in Santo Domingo), as well as in Brazil. Other economies based on slavery developed at the same time in the Americas, in line with successive cycles (coffee in Brazil, cotton in the United States, etc.). The plantation gave rise to an unequal and compartmentalized society, where hierarchies linked to the ethnicity barrier did not however, prevent a certain malleability. The slavery-based economy was a striking mix of early modern and archaic characteristics.

Venice and Genoa were already importing enslaved people during the Middle Ages, primarily Slavs—hence the word “slave”—of whom a minority were intended for the sugar economy (Cyprus). After 1453, the trade of enslaved people and slavery shifted from the Mediterranean towards the Atlantic. Soon, there were ten thousand African people in Lisbon; the Portuguese developed sugar production in Madeira and later in Sao Tomé, and the Spanish in the Canary Islands. The slavery-based economy finally reached the Americas: the use of African enslaved people was prompted by the decimation of enslaved native Americans, who were defended by the Dominican priest Bartolomé de Las Casas. The Spanish used African people in the fields, mines (Potosi), and Andean cities. In 1600, half of Lima’s population was Black. It was nevertheless in north-eastern Brazil that the use of enslaved people took a decisive turn, in connection with the sugar economy that had been developed there since 1550. By 1888, Brazil had imported at least a million enslaved individuals.

The ensuing cycle began in the Caribbean islands under the impetus of the Dutch. The rulers of north-eastern Brazil for a time, they left Pernambuco in 1650, with some travelling through Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Barbados, where their passage led to the rise of sugar cane production. This new crop replaced tobacco farming, which was initially based on a system of European indentured labour that generated tremendous abuse. In the late seventeenth century, plantations developed on the large islands (Santo Domingo, Jamaica), reaching their peak in the eighteenth century, when the enslaved population of the islands exceeded one million.

During the same period, the sugar economy was prosperous in Brazil (Bahia, Pernambuco), which concurrently developed the coffee economy (Rio, São Paulo). A plantation economy based on slavery appeared in the United States: tobacco in Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina, and rice in South Carolina. After 1790, the Old South began producing cotton, the primary crop of the nineteenth century. By 1865, 500,000 enslaved individuals had been imported to the United States. After the collapse of production in Santo Domingo—which represented 40% of global production in 1790—due to a revolt of freedom seekers, the sugar economy reoriented itself: the retreat of the French to Martinique and Guadeloupe, the resurgence of British Jamaica, and the lasting importance of Brazil.

The abolition of slavery in the colonies—1833 for the United Kingdom, 1848 for France, 1865 for the United States, 1886 for Cuba, 1888 for Brazil—put an end to a system that had led to the deportation of at least twelve million individuals.

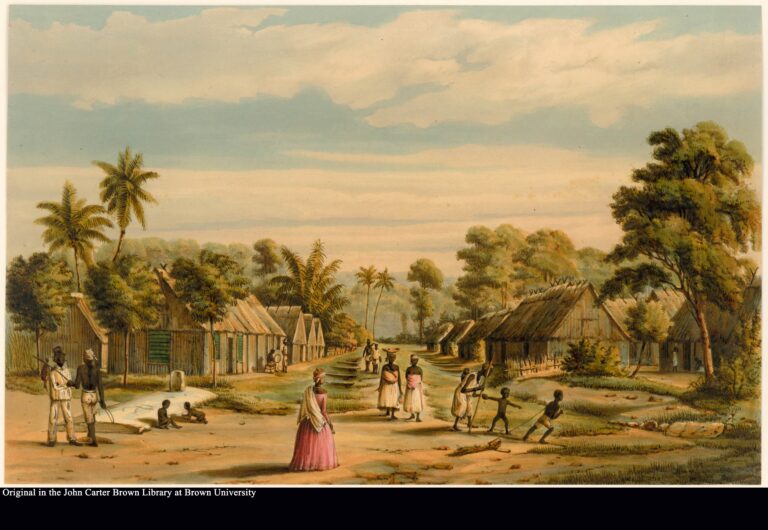

Half of the enslaved people in the colonies worked on plantations. Their average number per plantation varied: thirty of them in the cotton-producing Old South of the United States, fifty in the sugar-producing Lesser Antilles, and one hundred or more in Santo Domingo, where the size of farms increased in the late eighteenth century when sugar refining was added to farming, reaching an average of 261 hectares and 215 enslaved persons.

In Santo Domingo in 1666, Alexandre Oexmelin, a young French surgeon, observed two opposing scenes. On the one hand, was “a magnificent estate,” endowed with an intensive agriculture that offered the owners a comfortable lifestyle, whether residing there or in a city. On the other, were “miserable naked Black persons a pair of underpants their only clothing, incessantly burned by a hot sun.” The white population (“inhabitants”, small landowners, professionals, poor people, artisans) was highly hierarchical and diverse, as was that of the free people of colour. It became common to allow enslaved persons working in plantations—who were overseen by a manager and foremen, including some of colour—the use of a garden, thereby allowing the owner to reduce his food costs, while giving the enslaved peoples a small margin of autonomy (these were known as “Saturday gardens”).

Aside from some exceptions (notably in the United States), the insufficient rate of reproduction amongst enslaved people led to the increased importing of newcomers, only one third of whom were women. Women were in the minority in the white population as well, especially in the beginning, hence a métissage, particularly widespread in Latin America, that led to the appearance of free people of colour, some of whom married European women. For instance, everyone on La Réunion was of mixed blood, including “white” people. The barrier, however, increased during the eighteenth century, especially in the Caribbean islands, where after 1750 the rights of freed people of colour were gradually eroded.

White people, who were a minority on these islands, were much more numerous on the South American continent, where the colour barrier was less impenetrable, as well as in the United States.

Recent studies continue to show the harshness of the system. For example, in Brazil, the vision of a patriarchal order popularized by the anthropologist Gilberto Freyre in The Masters and the Slaves (1933)—one with less harsh interracial relations than elsewhere, a melting pot of Indian, Portuguese, and African contributions which formed the Brazilian nation—is being called into question today. Yet historians have uncovered the relative malleability of colonial societies and have acknowledged a certain agency on the part of the enslaved peoples, namely the capacity to appropriate legal knowledge which they turned against their owner, or the importance of African origins despite the Creolization of society.

Moreover, research insists on the permanence of a high frequency of marronage in particularly rebellious zones (freedom seekers or runaways who sought refuge in deserted places were called “marrons” [maroons]), and of an endemic smaller marronage (short-term absences).

The economy based on slavery exhibits a mix of modern characteristics (heavy investment, increasingly large farming units, high value-added productions which were the only ones compatible with the costs of transatlantic transportation), as well as archaic ones.

Today, the complexity and diversity of these societies is emphasized: that of the sugar-producing West Indies was not the same as that of La Réunion, where in addition to sugar, food crops and later spices were important. Enslaved people in cities and ports had more room to manoeuvre than those on plantations. The growing restrictions of the colour barrier did not prevent emancipation.

The debate regarding the impact of capital accumulation connected with triangular trade at the birth of the Industrial Revolution remains open.

Translated by Emma Lingwood

🔶 Article “À propos d’un projet en cours d’édition de manuscrits de Tombouctou et d’ailleurs” (revue électronique Afrique, 2015),

🔶 Islam et bonne gouvernance au XIXe siècle dans les sources arabes du Fouta-Djalon (with Georges Bohas, Abderrahim Saguer, Bernard Salvaing, Ahyiaf Sinno, Mamadou Alpha Diallo Lélouma). Paris: Geuthner, 2018.

🔶 Life stories from Guinea and Mali, including Bocar Cissé, Instituteur des sables: témoin du Mali au XXe siècle (with the participation of Albakaye Kounta). Brinon: Grandvaux, 2013.

About the authors

Bernard Salvaing is an Emeritus Professor of Contemporary History. His work initially focused on the history of Christian missions in Africa, and on the topic, he published Les Missionnaires à la rencontre de l’Afrique, Éditions l’Harmattan, Paris, 1995. He then specialized in the cultural history of Islam in Mali and Guinea, basing his research on Arab and Peul (Fula) sources.

Bibliography

Curtin, Philip D. The Rise and Fall of the Plantation Complex, Cambridge University Press New York, 1990.

De Almeida Mendes, Antonio. “Les réseaux de la traite dans l’Atlantique nord (1440-1640).” Annales ESC, 2008, vol. 4, p. 739-768.

Pluchon, Pierre. Histoire de la colonisation française, t. 1. Paris, éditions Fayard, 1991.

Régent, Frédéric. La France et ses esclaves, de la colonisation aux abolitions, 1620-1848. Paris, éditions Grasset 2012.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.