April 26 , 2023

Françoise Le Jeune

It was not until the end of the 18th century that the first abolitionist societies were established in Europe, whose members, intellectuals of the Enlightenment or evangelical Christians, aimed at putting an end to the slave trade. They sought to change the law, by organizing petition campaigns. In a second phase, new abolitionist societies, in the years 1820-1830, tackled the problem of slavery. Their members were shocked by the daily violence suffered by men, women and children on the cotton plantations. In both campaigns, Anglophones, both British and American, seemed to be the driving force behind the production of texts, imagery, and examples of collective mobilization to repeal slave policies in each state. In the 1840s, abolitionist societies joined together and formed an international movement.

If the trade and slavery of human beings did not seem to disturb the majority of Europeans for a long time, a form of moral awakening gradually took place during the second half of the 18th century, at a time when Britain and France seemed to be profiting fully from the slave trade.

A number of moralizing pamphlets were published confidentially, before being more widely disseminated among intellectual and religious circles, particularly in Britain, in the 1770s and 1780s. The driving force behind this new cause was the authors’ moral conscience. Most of them were evangelical Christians, particularly the Quakers who were upset by such trafficking in human beings and by their despicable exploitation in the plantation system. Several authors, including Anthony Benezet, a Protestant preacher, Thomas Clarkson, then an aspiring Anglican priest, and John Wesley, a Methodist preacher, contributed through their writings to denounce the trade, then slavery.

The late awakening of the right-thinking population in Europe, regarding such a trade was due to the fact that during all these years, few people were moved by the fate of the slaves and few individuals questioned the origin of the sugar or cotton they consumed. The circulation of moralizing texts denouncing the slave trade now triggered awareness among some intellectual circles.

In the English-speaking world, the first abolitionist writings came from the New England colonies, and particularly from Christian authors writing from Quaker Philadelphia. The transatlantic Quaker network then promoted the circulation of moral pamphlets all the way to Britain. For instance, Anthony Benezet with his texts condemning the slave trade as unchristian, awakened the minds of his contemporaries in Philadelphia, who put an end to the purchase of slaves in their community. In Britain, the reception of Benezet’s pamphlets caused a moral shock, even a religious revelation, in the English evangelical circles. Benezet denounced the slave trade and the brutality inflicted on bodies and souls of African captives. After him, John Wesley, a Welsh Methodist preacher who had lived in Georgia, an Anglo-American colony, criticized the moral decay of slave societies and the European slave economies that supported them. Eventually, according to these preachers, if the odious trade did not stop, European societies were doomed to divine wrath and slave owners condemned to damnation.

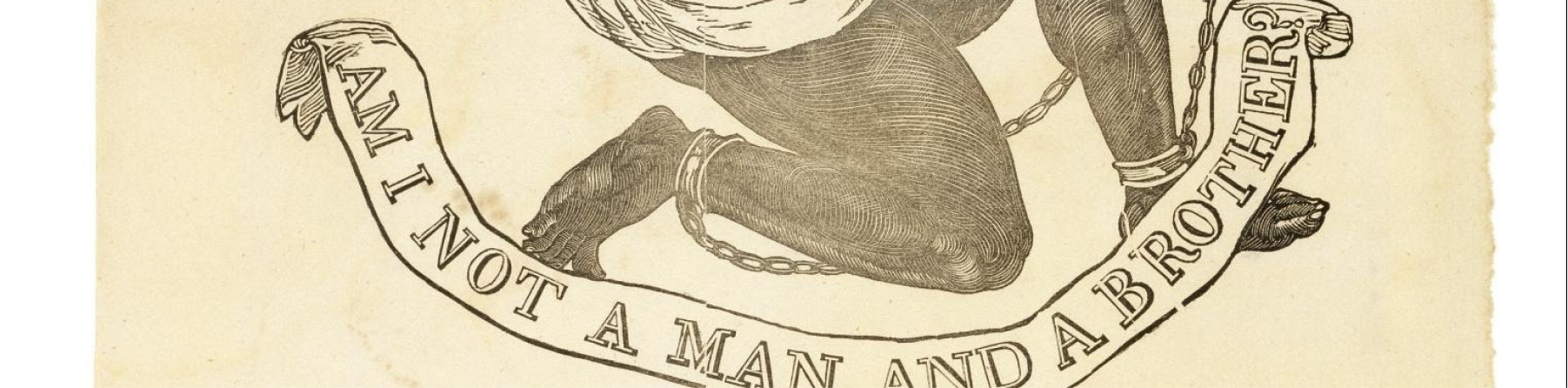

The first European abolitionist movement was then born in England, at the initiative of a group of evangelical Christian intellectuals, convinced that they had all received the revelation that they had to stop this sinful trade. The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in London in 1787. Its aim was to set up a political campaign, aimed at the general public first, to convince Parliament to put an end to the slave trade. The first step was to convince British people that black men and women were human beings, endowed with feelings and reason, brothers and sisters after all.

For this purpose, the British abolitionist society published texts and images denouncing the cruelty of the slave trade, the violence of the captains of the trading ships, the bestiality represented by the “Middle Passage”, and then it was necessary to speak about the humiliations experienced by slaves on the plantations, to describe the daily violence and cruelty against their bodies ravaged by the whip. The villains were denounced. Slave owners and ship captains were condemned by the general public.

Testimonies of those who participated in this traffic were rare, but in England, Thomas Clarkson took on the task of collecting a few accounts of sailors, surgeons or ship captains who had left the slave trade after having received the revelation.

Putting an end to the slave trade, which was the first mission of the British Abolitionist Society, and of the French Society “Les Amis des Noirs”, consisted first of all in persuading parliamentarians that the law had to be reformed, that the slave trade had to be prohibited, and that the protection of slave ships had to stop.

The British abolitionists’ first step was to bring Christian souls to feel the violence inflicted during the Middle Passage, or during the uprooting of African men, women and children from their native land. Abolitionists aimed at creating a feeling of compassion towards the slaves. They relied on shocking imagery, reconstructed from the testimonies collected on the slave ships. These images represented chained bodies, crammed into the holds of ships, and they sought to shock parliamentarians and the general public. The abolitionists must have relays and connections in Parliament. William Wilberforce, then MP, made a long speech in the House of Commons in April 1791. In France, Condorcet addressed the deputies in his text To the electoral body. Against the slavery of the Negroes. It was necessary to convince those who made the law, but also the public who signed petitions addressed to the members of parliament. The gist of these petitions made clear Africans were above all men and women, not beasts of burden. They had a soul, an intellect and the sufferings they endured must be stopped by all Christians.

At the end of the 1780s, the British abolitionists launched their campaign. First, they focused on the slave trade, which had to be stopped by law, hoping that the source of labour would dry up and that the economic model of slavery would gradually cease. Abolitionists denounced the horrible conditions on slave boats, and insisted on the shame such a trade brought to christian Britain. The goal was to convince the public that the nation, if its Parliament continued this odious traffic in human beings, would no longer be blessed by Providence.

The abolitionists, both French and British, had to face a powerful network of planters and merchants who formed a political and financial lobby, often protected by the aristocracy. They campaigned to convince parliamentarians they should preserve the slave trade and slavery.

In Europe, the slave revolt in Saint-Domingue in August 1791 brought the campaign against the slave trade to a halt, in Britain and France. Both abolitionist societies were in contact through Thomas Clarkson, who, at the beginning of the French Revolution, had made the trip to Paris. There he presented to the “Amis des Noirs”, the way he organized his popular campaign in Britain, and how he resorted to images and artifacts to convince sensitive souls to sign petitions against the trade. He even imagined creating a Franco-English abolitionist movement that was underway at the time of the French Revolution. Then, the abolitionists on both sides of the Channel were accused of being responsible for the insurrection in Saint-Domingue. They would have incited the slaves to rebel. In France, the members of “Les Amis des Noirs” were indicted, which put an end to the abolitionist movement. In Britain, the abolitionist campaign also lost momentum.

The slave trade was finally abolished in several countries at the beginning of the 19th century. But the vote which put an end to the slave trade in many countries (in the young American Republic in 1787, in the British Empire in 1807, or in the French Empire in 1815) cannot really be justified by the impact of the abolitionist campaign in the years 1780s-1790s, in Britain or elsewhere, as its momentum had dwindled in the wake of the Saint-Domingue insurrection. The end of the slave trade rather seems to be the result of new economic strategies prompted by commercial competition between empires.

Contrary to what British abolitionists imagined at the beginning of their campaign in the 1780s, the end of the slave trade did not lead to the decline of slavery, nor did American planters seem to be disturbed by the end of the African slave trade by European merchants. In the early 19th century, the economic model of slave societies flourished, allowing planters to amass wealth on sugar or cotton plantations in the Atlantic Ocean, on the American continent or in the Indian Ocean. The Christian speeches or the philosophy of human rights, denouncing the slave trade and slavery, which had awakened the abolitionists of the end of the 18th century, seemed long forgotten.

A second transatlantic abolitionist movement gradually took shape in the 1820s and 1830s among evangelical Christian networks between New England and Britain, at the initiative of a few well-known abolitionist figures (Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce) and newcomers like the American William Lloyd Garrison. In addition to these men, there were women, often described as “auxiliaries” in the new abolitionist movements, and a number of emancipated former slaves, like Frederick Douglass, who fought for their collective freedom in these racialized societies.

As in the first campaign, it was a matter of convincing parliamentarians (at Westminster, in the American Congress, in the French Assembly…) to put an end to slavery, by law. Abolitionists had to attack property, a sacred right in Common law. The campaigns against slavery launched by these abolitionist societies, aimed at bringing their supporters to sign popular petitions which would influence political representatives. It was necessary to again convince new generations, that black people were brothers and sisters, endowed with feelings and rights, and that planters were “monsters” whose violence will be punished by the Divine. Through texts and imagery, representing the miserable lives of slaves on the plantations, the general public rallied to the abolitionist cause in the English-speaking world. Abolitionist societies even created an international movement from the 1840s onwards.

But here again, the rallying of public opinion which was supposed to influence the opinion of politicians, seemed to count for little. Indeed, the vote to abolish slavery in the British Empire in 1834, as well as the abolition of slavery in 1863 in the United States, and in France in 1848, do not seem to be connected to a sentimental or humanistic approach, but rather to an economic context that no longer conceives of the slavery model of the plantation, as profitable. It was quickly replaced by a system of indenture servants, recruited in the Asian colonies to serve the plantations.

About the authors

Françoise Le Jeune is a Professor of North American and British history and civilization at Nantes University. Her research on the British Empire in the 18th-19th centuries, and on the revolutions in the Atlantic world, is part of Axis 1 of the Centre de Recherche en Histoire Internationale et Atlantique (CRHIA).

Bibliography

Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital, Foundations of British Abolitionism, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Paula E. Dumas, Proslavery Britian : Fighting for Slavery in an Era of Abolition, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Françoise Le Jeune et Michel Prum dir., Le débat sur l’abolition de l’esclavage, Paris, Ellipse, 2008.

Marie-Jeanne Rossignol et Bertrand Van Ruymbeke (eds), The Atlantic World of Anthony Benezet (1713-1784): From French Reformation to North American Quaker Antislavery Activism, Leiden, Brill, 2016.

Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780-1865, New York, Routledge, 2000.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.