The Quattro Mori monument: symbol of the trade of enslaved people and the enslavement in the Maritime Republics (Italy)

Luca Lo Basso

The great maritime republics, notably Genoa and Venice, were major mercantile and maritime nations that participated in the trade of enslaved people in the Mediterranean. Although most of these enslaved men and women came from North Africa, some, through the trans-Saharan trade, came from sub-Saharan Africa. The Quattro Mori monument in Livorno is symbolic of Italy’s history of slavery.

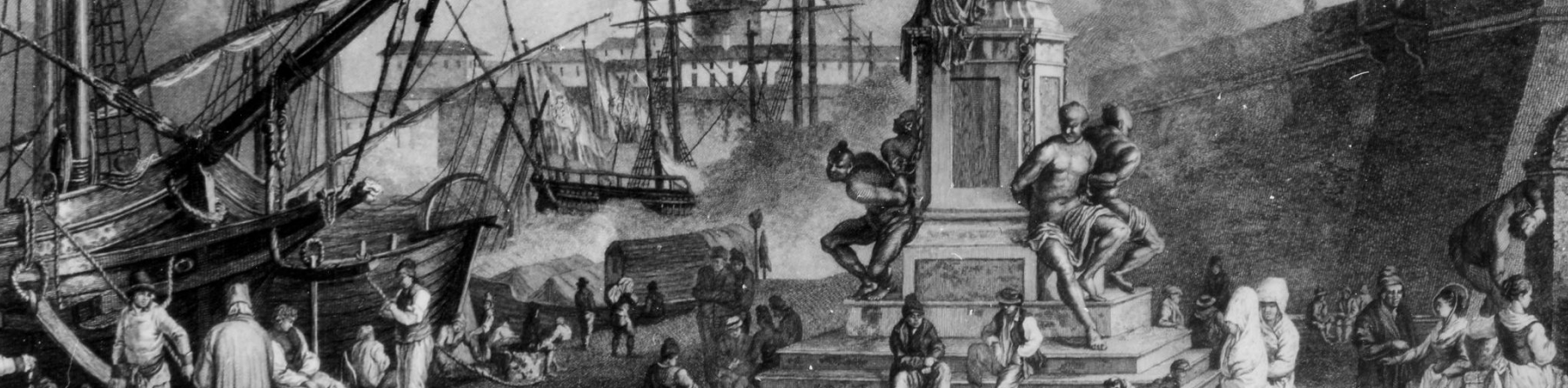

Even today, in front of Livorno’s old port, immediately against the ancient ramparts, you can admire a large marble statue of Grand Duke Ferdinando I de Medici, whose feet are shackled to four enslaved men. The monument, better known as the Quattro Mori, is an obvious representation of the phenomenon of Mediterranean slavery present in Italian cities in the modern era. The statue, commissioned in 1595 by the Grand Duke himself from the elderly sculptor Giovanni Bandini, was not completed until later, 1607, when Pietro Tacca was commissioned to design the study to complete the monument with the presence of four enslaved Berber men bound in Medici chains.

Who are Morgiano and Alì Salettino, and what were they doing in Livorno in the early 17th century? They were two typical enslaved men of the Mediterranean at that time, probably captured by the Christians during an attack or a naval battle, or bought at one of the many slave markets present in all the ports of the Great Sea. The phenomenon of slavery has been present in this region since antiquity, and in every era the fundamental element of this institution is the reduction of the human being to a tradable commodity, as provided for by Roman law.

Even within the context of later eras, the institution of the captis deminutio continues to be of particular importance, particularly in the modern era, as it was perfectly suited to the reciprocal captures that took place in the Mediterranean between the Christian and Muslim zones. The prisoner could then be bought back and thus return to freedom, whereas the slave, in theory, had to spend his life working for the owners, with no possibility of escape.

This is how it should be, at least in legal terms, but in the reality of the Mediterranean at the time, the two figures were blended and confused, with no way of determining who was the slave and who was the prisoner. What is certain is that thousands of Morgianos and Alìs were captured and forced to work, especially from the 16th century onwards, when confrontations between the Christian powers and the Ottoman Empire became increasingly intense.

Italian ports and cities – led by Genoa, Livorno, Naples and Venice – quickly became thriving markets for these enslaved men, mainly destined to serve as rowers on the galleys of the various fleets. In general, each Mediterranean fleet used a third of enslaved galley rowers for each unit, given that on average each galley needed around 250 rowers. These men had to be fairly young – between roughly 18 and 60 years of age – with a sturdy constitution and great endurance.

Slavery in Italian cities was not confined to men. There were many enslaved women present in the houses of nobles as domestic servants, often chosen for their beauty and dedicated more as mistresses than for housekeeping. The rapes and violence perpetrated against young women often ended in unwanted pregnancies, some of which occasionally gave rise to descendants of noble lineage, as in the case of Alessandro de Medici, known as the Moor, son of the famous Lorenzo il Magnifico (Lorenzo the Magnificent), and perhaps of a brown-skinned former enslaved woman.

All these enslaved persons in Italian cities only had two ways out of their condition: escape or purchasing their freedom Escape was very frequent, as one might expect. But it was not always possible to escape from the houses of the lords, the penal colonies or the galleys, even if these were anchored at port. Given the distances from their countries of origin, fugitives could easily be recaptured and put back to work in conditions of slavery.

On some rare occasions, escapes also had a happy outcome. This was the case for a group of six persons, enslaved after the capture of a privateer from Trapani in 1793, who managed to escape, thanks to the theft of a small boat in which they arrived safe and sound after a few days in the port of Biserta.

Italian cities, which have known the phenomenon of slavery since antiquity, saw an influx of new enslaved people, mainly bound to be used as motive forces on galleys. In particular, ports held numerous captive markets and took in large numbers of people, whose names and faces are often forgotten, with the exception of cases such as Morgiano and Alì, who became symbols of slavery, immortalized forever in the Quattro Mori monument, still visible today in front of Livorno’s old port.

About the author

Professor of modern history at the University of Genoa and director of the Naval and Maritime History Laboratory (NavLab), Luca Lo Basso specializes in maritime history and the history of the Mediterranean in the modern era. His main research topics are navigation and trade in the Mediterranean, the Genoese presence in Atlantic trade in the 17th Century, slavery in the Mediterranean, naval warfare and raiding in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Bibliography

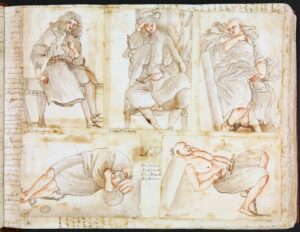

AGOSTINI A., Istantanee dal Seicento. L’album di disegni del cavaliere pistoiese Ignazio Fabroni, Florence, 2017.

BONO S., Guerre corsare nel Mediterraneo. Una storia di incursioni, arrembaggi e razzie, Bologne, 2019.

FRATTARELLI FISCHER L., Il bagno delle galere in “terra cristiana”. Schiavi a Livorno fra Cinque e Seicento, in “Nuovi Studi Livornesi”, vol. VIII (2000).

LO BASSO L., Uomini da remo. Galee e galeotti nel Mediterraneo in età moderna, Milan, 2004.

MANDALIS G., I Mori e il Granduca : storia di un monumento sconveniente, Livorno, 2009.