March 27, 2023

Alessandro Stanziani

The history of slavery in modern times is not limited to the Atlantic slave trade; it encompasses the slave trade in the Mediterranean and Central Asia, on the one hand, and the experiences of enslaved “whites” across the Atlantic in the 17th century, on the other. The slave trade connected to the plantations continued into the 19th century, and from the middle of that century onwards, was accompanied by more or less forced forms of immigrant labour, particularly from Asia, destined for the Americas, but also for the Indian Ocean. In the 20th century, international institutions preferred to use the term “forced labour” rather than “slavery” to highlight the ruptures that had occurred, all the while minimizing the continuities.

It would be wrong to associate slavery solely with the rise of plantations in the Americas and the trade in African captives. Since medieval times, several European powers, like Venice, Genoa, and later Spain (already veritable empires), had colonies in the eastern Mediterranean and bought slaves from Russia and Central Asia, as well as from India, along with Muslim captives. These enslaved persons were then put to work on the first sugar plantations of the time (in Tyr, Candia, Sicily, and on the Middle Eastern coast) or in mainland France where they were mainly employed as servants. Between the 14th and 19th centuries, some six million enslaved persons transited between Central Asia, India, and the Mediterranean.

With the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, procurement from Central Asia became more difficult; from the 16th century onwards, Spain and Portugal extended their supply chain to northern and western Africa. This traffic also extended to the Portuguese islands of Madeira and Cape Verde where sugar plantations were in the process of being established. In the second half of the 16th century, the Portuguese acquired some 80,000 enslaved persons per year along the western coasts of Africa, to which they added 41,000 per year destined for the Americas. For their part, the Spaniards sent almost 100,000 enslaved persons to work in their mines and plantations in America between the late 15th and late 16th century.

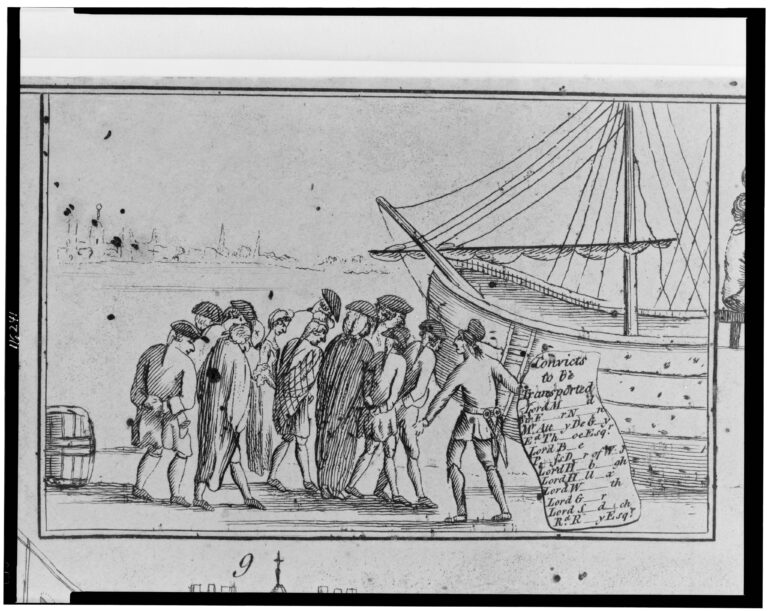

At the same time, the English established a plantation system in one of their first colonies: Ireland. The “Ulster plantations” were based on a form of extreme servitude. Local peasants were used for labour under the yoke of the English, with the help of a few allied local landowners. This enslavement of “whites” subsequently became generalized. During the first half of the 17th century, France and England forcibly recruited European “migrants”—indentured labourers in England (a disguised form of slavery)—whom they sent to their American colonies. These contracts stipulated that the captain or the purchaser in the colony advanced the price of the voyage for the labourer-migrant, and in exchange, the latter worked for free for a period of seven years. During this period, he could be transferred or sold, and was forbidden from marrying without the permission of his master. His debt was liable to increase because of any number of presumed violations. Between 1610 and 1660, 170,000 to 225,000 indentured migrants left the British Isles for the Americas. Another 500,000 followed between 1630 and 1780.

As for France, the numbers were much lower: approximately 50,000 indentured migrants, all destinations combined, between the 16th and 18th centuries. The main reason for this was that the voyage across the Atlantic was viewed as an even harsher punishment than imprisonment for vagrancy or possible starvation in France.

Another difference with England lies in the role of women: on the English side, while men were largely in the majority, indentured families (women and children) were also numerous. On the French side, on the other hand, it was almost exclusively single men who embarked on the voyage. The authorities subsequently sought to recruit women, especially for New France (Quebec). These women were taken from hospices, convents, and prisons. In other words, only those women considered as reproachable and “without morality” were sent and married by force to emigrants, often soldiers or criminals. Only a handful of them survived more than a few months out of the 800 individuals sent between the 1650s and the 1670s.

It wasn’t until the second half of the 17th century, with the rise of plantations, that the slave trade fully emerged. The main European powers began to get involved. There were many reasons for this: there weren’t enough indentured labourers for the growing needs; moreover, the latter were increasingly rebellious. The colonizers also considered that the physical conditions of “whites” did not make them especially suited to the local environments or to the cultivation of sugar. In total, some twelve million enslaved individuals landed in the Americas between the 16th century and the 1870s. If, in the 17th century, Spain and Portugal were the main actors of the transatlantic slave trade, in the 18th century, France emerged as the third power, but still far behind the Portuguese and the British who dominated affairs. Finally, during the first half of the 19th century, up until the official abolition of slavery in the British Empire (1830s) and France (1848), and despite the prohibition of the slave trade by the British in 1807, trade nevertheless continued. Three and a half million enslaved Africans arrived in the Americas, mostly (2.4 million) on Portuguese ships.

In reality, these networks were global. In the Indian Ocean, an important slave trade linked to the rise of Islam had been in place since the 10th century. It is worth emphasizing the omnipresence of servitude and enslavement in such regions, connected to debt. For example, enslaved persons circulated across Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Arabian Gulf, and East Africa. Between 1400 and 1900, 2.5 million enslaved persons were sold along the coasts of the Indian Ocean, and 9 million via the trans-Saharan route. The latter, intended almost entirely for the Middle East, were also partly monopolized by European merchants. Similarly, the British, once India was occupied, made use of local forms of slavery, and then introduced forced labour for the construction of infrastructure and the development of tea plantations in Assam.

The abolitionist movement developed slowly, firstly in the United Kingdom (late 18th – early 19th century), much later in France (mid-19th century), and even later in Spain and Portugal (second half of the century). In conjunction with this process, in order to cope with the shortage of both labour and cash for landlords, France and the United Kingdom returned to the use of indentured contracts, common in the 17th century. Only, this time, it was mainly Indians and Chinese (known as “coolies”) who were recruited. Presented as free contracts, in reality, these relationships reproduced the characteristics of slavery in many respects, and were only prohibited during or after World War I. Between 1850 and 1914, 11 million Chinese emigrated to Southeast Asia (British and Dutch lands), in three quarters of these cases, they signed indentured contracts, the remainder were financed by family networks and villagers. Two million Indians migrated mainly from Bengal to British colonies: Mauritius, in southern Africa and towards the Caribbean. To this number, we can add 1.5 million who emigrated to Ceylon and another 2 million to Burma.

Finally, from the 1890s onwards, the European powers who had just divided up Africa, justifying their actions by the need to abolish slavery there, were nevertheless quick to subject the local populations to coercion and forced labour. Of an extreme nature in the Belgian Congo, similarly violent approaches were adopted in the French Congo, Ghana, and South Africa.

During the 1920s, the League of Nations and one of its offshoots, the ILO (International Labour Organization), declared slavery to be officially abolished and announced that they wanted to do more against forced labour. This nuance is worth highlighting. However, none of these treaties and recommendations were really applied and decolonization ended without any real labour laws and forms of social security being implemented in the former European colonies.

Translated by Emma Lingwood

🔶 Co-directed by Gilbert Buti, Daniel Faget, and Solène Rivoal, Moissonner la mer. Économies, sociétés et pratiques halieutiques (xve–xxie siècle). Paris/Aix-en-Provence: Karthala/Maison méditerranéenne des sciences de l’homme, 2018.

🔶 Co-directed by Gilbert Buti and Luca Lo Basso, Entrepreneurs des mers. Capitaines et mariniers du xvie au xixe siècle. Paris: Riveneuve éditions, 2017.

About the authors

Alessandro Stanziani is director of studies at the EHESS and head of research at the CNRS. His work focuses on the history of labour (Russia, Western Europe, Indian Ocean, 17th-19th centuries), global history, the history of food and capitalism. He has written the following books: Capital terre. Une histoire longue du monde d’après, XIIe-XXIe siècle, Paris, Payot, 2021; Les métamorphoses du travail contraint, Paris, Presses de Sciences-Po, 2020; Les entrelacements du monde, Paris, CNRS éditions, 2018; Histoire de la qualité alimentaire, Paris, Seuil, 2015; L’économie en révolution, Paris, Albin Michel, 1998.

Bibliography

Eltis, David, Engerman, Stanley, Drescher, Seymour, Richardson, David (ed.). The Cambridge World History of Slavery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 4 vol., 2013-2017.

Stanziani, Alessandro, Bondage. Labor and Rights in Eurasia, 16th-early 20th Century. New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2014.

Stanziani, Alessandro. Les métamorphoses du travail force. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, 2018.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.